Does this Study Prove that Law Firm Partners are Racist?

Published: Apr 22, 2014

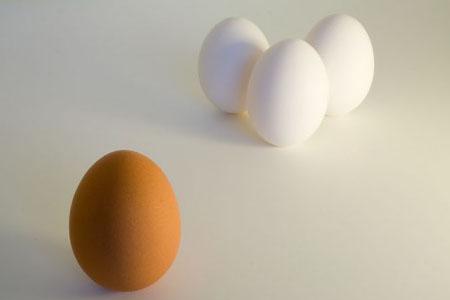

So it turns out that partners at law firms are racist, and they don't even know it. The legal industry, particularly, BigLaw, has long struggled with diversity. While improvements have been made in the hiring of diverse associates, many law firms still fail to retain and promote minority and female associates. Associates who participated in Vault’s 2013 Law Firm Associate Survey, a survey of nearly 17,000 associates from over 150 large and mid-sized law firms from across the United States, repeatedly commented that the partnership ranks at their firms were overwhelmingly white and male. A new study by Nextions may reveal a contributing factor to the persistent whitewashing of the upper echelons of the legal industry.

The Nextions study found that law firm partners demonstrated an unconscious or implicit bias when evaluating the writing of a male African American associate. The Nextions team and five partners from five different law firms created a research memo from a hypothetical third-year litigation associate deliberately inserting 22 errors. The memo was distributed to 60 partners from 22 law firms who had agreed to participate in a “writing analysis study.” Twenty-three of the partners were women, 37 were men, 21 were racial/ethnic minorities and 39 were Caucasian.

The cover email asked the partners to edit the memo for factual, technical and substantive errors as well as to rate the memo from a 1 to a 5, “1” indicating that the memo was extremely poorly written and “5” indicating that the memo was extremely well written. For half of the evaluating partners, the cover email indicated that the writer was African American, while the cover email for the other half indicated that the writer was Caucasian. Both of the hypothetical writers were named Thomas Meyer and both attended NYU Law. Fifty-three partners completed the evaluation, 24 evaluated the African American associate and 29 evaluated the Caucasian associate.

Although the partners were given identical memos, those given the memo written by the African American Thomas Meyer found more errors and provided a lower overall evaluation of the memo. The African American Thomas Meyer received an overall 3.2/5.0 rating, and the Caucasian Thomas Meyer received an overall 4.1/5.0 rating. Additionally, although evaluators were not asked to edit or comment about formatting, 29 sought formatting changes from the African American associate in contrast to 11 who sought changes from the Caucasian Associate. No significant correlation was found between a partner’s race/ethnicity or gender and the patterns of errors found between the two memos, although female partners generally found more errors and provided longer comments than male partners.

These findings indicate that if partners have lower expectations for an associate, they are more likely to read the memo with a critical eye or be less likely to overlook errors. The partners who expect to find fewer errors, find fewer errors, and those who expect to find more, find more.

Perhaps the partners evaluating the African American Thomas Meyer were simply more critical of all junior associates’ work or had a heightened attention to detail. To control for this, all partners participating in the study could be given two memos discussing the same issue, one “written” by an African American associate and the other by a Caucasian with the same number of similar errors.

Although the metrics of the study may not be perfect, the findings are still startling. Partners may be more critical of the African American associates’ work because partners believe it will be written poorly before they even read the first sentence, it seems, even if the partners themselves are a member of a minority. Unlike exams at many law schools, work product at law firms and decisions regarding associates’ career trajectories are not blindly graded. Although many factors other than the actual quality of associates’ work (personality, demeanor, hygiene etc.) may be considered when bonus, salary and promotion determinations are made, less favorable reviews of associates’ work because of unconscious bias puts African American associates at a disadvantage from the start. Law firms, therefore, should not be surprised at high attrition rates among African American associates when they are providing the same or better quality work product as their Caucasian counterparts and not reaping the same benefits. Recognizing unconscious bias on the part of law firm management and partners may be a positive step toward creating a more inclusive legal profession.

Do you think unconscious bias occurs at your law firm or in your office? Let us know in the comments.

FOLLOW VAULT ON TWITTER @VAULTLAW and INSTAGRAM @VaultCareers!

LIKE US ON FACEBOOK!

Read More:

The Overall Best Law Firms for Diversity

Diversity and Its Impact on the Legal Profession

Yellow Paper Series: Written in Black & White – Exploring Confirmation Bias in Racialized Perceptions of Writing Skills